- Home

- Brett Pierce

Beyond the Vapour Trail

Beyond the Vapour Trail Read online

Brett Pierce

Beyond

the

Vapour

Trail

The beauty, horror and humour of life

An aid worker’s story

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

www.transitlounge.com.au

Copyright © 2016 Brett Pierce

First Published 2016

Transit Lounge Publishing

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher.

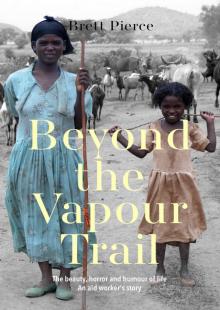

Cover image: Brett Pierce

Cover and book design: Peter Lo

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

A cataloguing-in-publication entry is available from the

National Library of Australia: http://catalogue.nla.gov.au

ISBN: 978-0995-3594-2-0

‘Well, when I write my book, and tell

the tale of my adventures – all these little

stars that shake out of my cloak – I must

save those to use for asterisks!’

—Edmond Rostand, Cyrano de Bergerac

For my children Bethany, John, Jared and Ciarán

For my mother, Iris

And especially, for Kathie

Foreword

I remember as a young child, long before I could read, sitting with picture books, leafing through them, drawn in by the images. Trying to decipher Babar or my grandmother’s Russian folktales with the most beautiful Evgenii Rachev illustrations. I could see that each image was somehow connected, that there was a story unfolding, but I had to create the narrative myself. Something inside me demanded meaning.

We experience life through an array of impressions, images, encounters and happenings, while we struggle to make sense, searching for the story hidden in the subtext. My years in overseas aid have brought an immersion in so many places, images, cultures and experiences. Over twenty years I travelled until I became ‘a vapour trail in a deep blue sky’. I entered overseas aid amid a slide into fifteen years of chronic depression, my beliefs and world view fracturing, and then a slow but real recovery — simply struggling to understand the text under my experiences.

Maybe reflection is one of those lost spiritual disciplines we absent-mindedly tossed out with everything else when we grew up and became too big for religion. Our experiences are so immediate and fleeting. It takes distillation to draw out words to describe what they mean to us, to connect with something inside us.

Writing this book has been an opportunity for me to piece together a narrative from my travels. It’s not enough to just encounter the world: we must decipher what it etches on our souls.

CHAPTER 1

The question in the back of your mind

It might look something like this: the image of a gun being pointed at you. How long would it take to breathe your next breath? How would you respond to a person holding your life in their hands?

There are places where, for a brief time, things fall apart and we see what people are capable of when the rules no longer seem to matter. But not usually when I’m there. I dismiss it as unlikely and get on with things. So the idea sits quietly in the corner like a spider, and descends when I’m not expecting it, a mental picture when I’m jet-lagged or half-asleep.

Clearly no-one has killed me, although I have had a gun pointed at me.

Apparently.

I was in Phnom Penh a few years ago and walked down to the Mekong River for a meal. There’s something about any stretch of the Mekong that mixes well with gin, tonic and sunset. Not all of them in the glass, obviously. Or a cold Beerlao – for me, Asia’s best beer. So being alone one particular evening I found a suitable cafe, sat outside, ordered a meal, and took in the gentle flow of the river behind the slightly faster flow of people wandering past – two streams of horizontal movement as the sun slid downwards, pulling all the blue away as it went. The service was friendly, the beer was cold, the food was hot and good. The girls at the next table were animation and laughter, although I didn’t register when they left the table and went inside. I couldn’t hear them because a motorbike had paused on the footpath right in front of my table. I kept eating. Then I glanced behind me and noticed they’d closed the cafe doors, but the restaurant wasn’t closed so that didn’t really make sense. None of these impressions formed comprehensible thought. I was in my own world.

I vaguely became aware that all the outside tables were now empty, and so I glanced behind me again. The doors were not quite closed. The waitress and one of the girls were peeking through a crack in the door and waving. It looked like they were waving to me, but since I didn’t know them I assumed it was to someone else. It was all like background noise. Then I spotted a guy on a table at the next cafe. He was on the ground and then he ducked in to a shopfront. Now that was odd. I turned around to check if they were waving to someone behind me. A guy right in front of my table was putting a gun away into his jeans back pocket as he jumped back on a bike with his friend and they motored back into the street.

Well, that doesn’t count, because I didn’t even know he was pointing a gun at me. I must have been a serious wet blanket for his show. Everyone else was ducking for cover wherever he pointed and the guy sitting immediately in front of him was oblivious, like the proverbial mad dog or, God forbid, Englishman. Just eating. When I did see him, he didn’t look particularly frightening because he’d lost interest. He was probably just enjoying the power of his bravado and had given up on me as not being in the least entertaining. But given his age, and that this was Cambodia, who knows where he had pointed a gun in the past, and how much freedom he’d had to use it. Or whether he’d simply faced the cold stare of a barrel too many times during the Pol Pot era, during the Long March, the apocalyptic madness, when using it or not had little consequence. And perhaps he wanted a chance to feel the dice in his hands. He didn’t roll it, he just rattled the cup.

So I didn’t know he was there, but my reaction was close to what I had decided I would do if it ever happened. Falling to the ground sobbing, begging for mercy probably doesn’t make any difference. Somewhere I concluded that the one thing I didn’t want to give to any person who was going to kill me was my dignity. If I can’t prevent it I would rather die well. But you really have no idea how you’re going to behave until the situation happens along.

Yet I asked myself this question one night in Uganda, going to sleep in the dark with a rebel army only a few kilometres away. I remember trying to decide what my move would be if I was woken in the night.

And Sierra Leone was another close call.

CHAPTER 2

Sierra Leone

Flying into Freetown has an interesting twist to the arrival. You haven’t arrived. The airport is on an isolated peninsula near Lungi and you still need to travel to get to Freetown. I couldn’t imagine why they built the airport there. Perhaps when they built it they hadn’t pictured multiple chartered flights per day of big planes with hundreds of people. All stuck on an isolated peninsula wanting to get to Freetown.

It’s a whole rigmarole to get off the peninsula. You can water taxi with twenty to thirty locals in a motorboat with its gunwales so low it feels like it’s almost underwater. It takes an hour. The hovercraft takes … well, I’m not sure, but it’s much quicker than water taxi. You can take the train … no, wait. They shut that down in 1974. There’s a ferry to Kissy that takes an hour and still leaves you two to three hours’ drive short of your destination through god-awful traffic. Or, as I did, you can take the quick route, a helicopter. Nice Russianbuilt helicopters with Russ

ian-built pilots to match.

There’s a cold functionality to any Russian technology, and as I climbed into the chopper it seemed a little spartan and bolted together. It was noisy and not exactly luxurious, but it worked. As we lifted off it was slightly off-putting to get a clear view of wrecked helicopters nearby, but comforting to learn that the crashes had occurred with the old helicopter company. We were flying with the new company. Which, coincidently, bore a striking resemblance to the old company in both equipment and personnel. And more recently I heard that this entire helicopter service was closed down for similar reasons to the old one. Helicopter crashes.

Sierra Leone’s violent past confronted me immediately after my helicopter landed – safely – in Freetown. Usually at airports anywhere there are people clamouring to help you, so someone speaking to me doesn’t particularly grab my attention. This one did.

‘Can you help me?’ came a voice behind me.

I turned, and a young man held up his two arms, minus both hands. From his age it was clear that he had been just a child when he was asked the brutal question: ‘Long sleeves, or short sleeves?’ The government had held a campaign to ‘put our hands together to build the country’, so the rebels systematically, and with vicious irony, cut off people’s hands. The brutality of that war is almost incomprehensible. Nearly half a million people were either killed or mutilated between 1991 and 1992. There are reminders of horror all around, and the people seem to manoeuvre around these memories and personal scars to live desperately normal lives. They are quietly inspirational.

We had come to test a new workshop we were developing, a training module that has since trained more than fifty thousand staff, local community partners and volunteers around the world. It involved paradigm change, transformative learning – a branch of education that turns parts of our world inside out to see them differently. In 2008 we were still testing and refining the training with local staff and community volunteers in Freetown. The group were bright, fun and outgoing. It was going to be a great workshop. Grace, an adult-learning consultant from the Philippines, decided to open her session with a story from the group.

‘Children are unique, aren’t they. Who can share a story of why children are unique?’

A guy called Ambrose absently put up his hand. What followed was his immediate, unreflected response to the question, the first thing that came to mind. So he told this story.

During the civil war Ambrose was a young man with a group of about seventy people fleeing the country. They were trying to escape to Guinea. The world as they had known it had fallen apart. He had lost contact with most of his family, but his parents were with him, along with a six-year-old boy and another relative. They had so far managed to avoid running into anyone. The rebels could be anywhere and travelling on the roads was risky, so they always scouted an area and then would quickly cross any open ground until they could find cover. They had been travelling like this for many days.

One morning they were crossing a clearing. Suddenly they heard shouts and soldiers came running out from the bush with guns pointed at them, screaming at them to lie down. Within moments they were lying with their faces on the ground, surrounded and helpless. The soldiers were mostly teenagers and boys, just a few adults among them.

‘Stand up! Stand up!’

They were informed that they were all going to be executed. Ambrose glanced up at some of the rebels and instantly recognised one of them. He was a neighbour, just a lad who had lived close by. The young soldier noticed him staring and looked up.

‘You! I know you!’ said the young soldier. He approached Ambrose.

‘Why are you here?’ he asked, ‘You should have gone to Guinea.’

‘We’re trying to go there now.’

He consulted some other soldiers.

‘OK, tell me who are your family, and we will let you go. The rest of them we will kill.’

Meanwhile, they got them to put all their luggage in the middle and set fire to it.

Ambrose told us that, being a Christian, he couldn’t stand by if he could help the others.

‘So he asked me who my family were – there were five of us. But I felt sorry for these people, so I told him, “All of these people are my family group.”’

‘“If you are lying to me, I will shoot you.”

‘My mother and father started crying. Then he took a child from my family, and asked him if he knew one of the people. He said no. So he mixed us all up and asked the child to identify who he knew. He picked out the family – the four of us. Then he asked if he knew anyone else. “No,” said the boy.

‘So they immediately killed all the rest.’

‘So,’ Ambrose told us in the workshop. ‘To me this illustrates that a child is unique because they cannot lie.’

I saw Grace’s face. It hit her. I looked at Ambrose, and then at the faces of my colleagues from Sierra Leone and wondered at the things their eyes had seen, what it meant to live in a world gone mad. He wasn’t trying to shock us, make us sad, tell us a horrific story. He just drew a story from his life based on an innocent question.

I began to wonder how these people were functioning after all the things they had seen and experienced. How was it that they were even remotely interested in our workshop, in work, in daily living?

It left me in awe. I wanted to take off my shoes, like I was on holy ground, because these people humbled me.

I spent weeks unable to deal with that story because I knew Ambrose. I shoved it away in the back of my mind because I couldn’t face it. As the week of the workshop went on, hints and bits and pieces of their lives slipped through. One of the fun parts of the workshop is built on a simple idea – if you want to work with children effectively, you need to remember what it feels like to be a child. So for one session, everyone becomes a six-year-old. They put paint on their hands and make a butterfly from their handprints. It’s all about them. It’s experiential and fun. It’s tactile and messy. People always remember that session. It’s just one session. But in Sierra Leone, they continued to be six-year-olds for the rest of the workshop – pulling hair, joking, role-playing, enjoying. It was another glimpse. In a twenty-year civil war, it was like the childhood most of them hadn’t experienced. Because of war.

Two years later, in 2009, I returned to Sierra Leone on a second visit. My local colleague Samuel picked me up at an impolitely early hour the next morning for an eight-hour drive to a small village deep into the east of the country, towards Guinea. Tombodu is a long way away from my home – it was a fifty-four-hour door-to-door trip without any stopovers – just transit and travel.

We drove east for many hours and began to enter the diamond-rich Kono District, passing through Koidu town’s main streets, studded with diamond merchants. It would still be another couple of hours before we arrived in Tombodu. It was a small village in a thickly wooded area, with concrete buildings, many still burnt out and abandoned from the war. Scattered around it were mullock heaps from the mining, which made it look exactly like a scene from the movie Blood Diamond, where Solomon was held captive with others to mine for diamonds at gunpoint. The locals who saw Blood Diamond told me they thought its portrayal of events in Sierra Leone was quite accurate.

We pulled up in the middle of the village. I had to jump out of the vehicle with my luggage and carry it straight into the meeting room because everyone was waiting for us to start. Our Sierra Leone office had chosen Tombodu because we were just commencing our work here, and key staff from across Sierra Leone had come. I was pretty excited about this training because of recent breakthroughs we’d had in Armenia and Albania on making child sponsorship very powerful in community contexts. I put my case down and immediately began the workshop. We began to explore the principles and tools together, and the local staff picked up what resonated and we looked at ways to contextualise the approach for this very different world.

The workshop continued through the afternoon without a hint of what was about to happe

n.

It was later in the day, about quarter past five, and there was now a hum of activity in the room as small groups were working together, so I finally found a moment to look out at the small community we were in. Large windows on three sides of the room had only metal grilles and looked out over the village. The heat clung and made my thin shirt feel like canvas. I pulled my shirt away from my skin, wet with perspiration, trying to catch any faint movement of air. There was none – the air was motionless.

As I glanced out, this village seemed different and I didn’t know why. I saw concrete buildings and mud huts, but only a few people, and they gave me furtive looks. It felt odd. Usually in any African village there are children hanging around, big smiles, wanting eye contact but then giggling shyly when you meet their gaze. This game wasn’t happening. It was late afternoon and, well, it just looked like typical west Africa in many ways – the slow rhythmic pounding of millet with a long thick pole in a small container on the ground, the counter rhythm of someone close by, slightly out of time, pounding their own grain, preparations beginning for evening meals … But I sensed distance, as if the people were holding me at bay with their eyes. The thought struck me that this was the hub of more brutality than I could comprehend. I looked at the group of women and wondered what else was behind their eyes, what horrors they had seen that could never be put into words.

The usual village sounds drifted in. Children’s voices, talk, animals and a general hubbub like a small market in the distance, which seemed to be getting louder. When I turned my attention to the crowd noise I began to realise there was a group somewhere in the distance yelling like a football crowd, but on the move. And it was approaching.

Suddenly the noise broke open behind us and I turned and saw through the windows on the opposite side a group of men. Running through the village. Straight at us. Maybe thirty. No, even more were coming around the corner – forty or fifty men armed with long sticks and tree branches and God knows what else. And headed straight towards our building. Angry.

Beyond the Vapour Trail

Beyond the Vapour Trail