- Home

- Brett Pierce

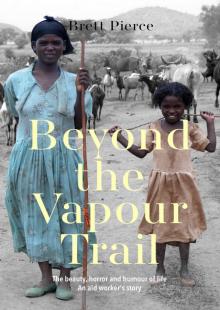

Beyond the Vapour Trail Page 19

Beyond the Vapour Trail Read online

Page 19

So this park held a few hyenas and lions behind fences. The wardens were about to feed them, and one of our African staff members, John, was there with us.

‘These lions are not wild,’ he observed.

I looked at them.

‘Yes, but if I jumped the fence they would kill me.’

He smiled. ‘Yes, they will kill you.’

‘So why do you say they are not wild?’

‘Because a wild animal,’ he said with an intense look, ‘always looks you in the eyes, to see what you will do next.’

As he said this, he looked me in the eyes. I looked at his features and spotted the familiar gap in his lower front teeth, and remembered he was originally from Kenya.

‘You are Maasai, aren’t you? Why weren’t your ears cut?’

The Maasai men have distinctive features from their initiation: the gap in their teeth, and their earlobes cut and elongated into a loop. From a distance you think they are long earrings hanging from their ears, but it is their earlobes. They are long enough that I recall one man hanging them over the top of his ears.

‘I was away at school for that ceremony, so I missed it.’

‘So, the lions are afraid of the Maasai, right?’

‘Of the men and boys. But not the women and girls.’

I thought this seemed particularly gender-insensitive of the lions.

‘So you looked after the cattle as a boy? By yourself? Did you see lions?’

‘Yes, of course. I saw lions. They would come close and walk up and down near the cattle.’

‘But you were just a child. Why didn’t they attack?’

‘The lions respect your space. They won’t come into our space. But of course, you must never enter their space or they will respond immediately. Also, they are dangerous if they have a cub. The cubs are always playful. They can’t tell that you are not actually an animal. You may find a female lion with cubs, and the puppies [sic] will run to you, and they get excited, they want to play. And the mother will take you down because of that. They are very protective.’

John grew up in Maasai Mara, in southern Kenya. He was well educated, a professional communicator, but he also carried deep knowledge about other things, from another life.

‘We had no neighbours, because the nearest neighbour was like ten kilometres away. So I grew up knowing animals, sometimes more than people. You totally know animal behaviour because you are with them all the time. At night you can never totally sleep because the lions might raid the boma. The thing is, you need to stop the cattle from breaking the fence – you need to stop the stampede. So the way to stop the stampede is to get out of the fence and get the lions out, just get them away. Mostly with fire. You have firewood and you just throw it. When they see it, they don’t like fire, they don’t like fire or light.’

‘So John, when you rush out in the night to do that, is it excitement? Is it fear?’

‘It’s … it’s adrenaline. I mean, you know if you don’t do it, you’re going to lose a lot by morning. This is why you keep the cattle protected. The lions follow the wind, so they go to the side where the wind will bring the scent to the cattle. And once the cattle smell the scent is coming from this direction, they run the other direction. Only one lion is on this side, and the others are on the other side. But you can tell when you get out of your house, you know how the wind is blowing. I’ll know where they are, and I’ll know how far they are. If the wind is not strong enough, they will probably come almost to the gate, they’ll probably step on the gate and just make sure the cattle will see, and there’ll be a stampede. And the most timid cattle always break the fence and run off. Always the youngest who don’t have the experience of the older ones. The older ones will probably try to remain within the fence.’

‘Do hyenas ever attack?’

‘Hyenas? No, they don’t attack the cattle unless it’s a lost cow. If you lose one cow and it’s there overnight, the group of hyenas will come, but they rarely attack. They just stay around there and intimidate it. If it tries to run, they will get it, but if the cow doesn’t run they just stay with it.’

I remembered being caught out in the pitch dark in Kenya with the threat of hyenas. Since I had been told years before what to do if I saw a lion or a leopard, I decided to expand my inventory of emergency tips. Just in case. ‘If you see a hyena or group of hyenas, what should you do?’

‘Mostly noise is enough for hyenas to run off, or just throw a rock at them. They mostly attack sick animals. Hyenas don’t attack, let’s say homes, in groups; it’s always a lone hyena. So if he comes in, he will not use the same strategy as the lions. He’ll come right in and take something. The risk with the hyena is, if he comes into a pen with many cows or goats, in the excitement he might just end up killing so many. Because of the greed, he will kill this one, and then suddenly sees the other one is running and he will go after that, and oh, sees another one. So he might just kill twenty or a hundred of them. Yes, it’s terrible. Sometimes you wake up in the morning if you don’t hear, it has killed so many goats. And only ate one!’ he laughs. ‘Yes, it’s sad,’ he continued. ‘That’s the downside. The lions don’t kill in greed.’

He told me that, despite his education taking him away, he had walked through the stages of the passage of life, and become a moran. He had faced lions.

‘People always think that they kill lions and that it’s easy, but … I mean, I saw people get hurt so badly. You don’t just kill lions, they fight back, and if they get you, goodness … God help you!’ He laughed again. ‘I mean, I’ve seen people …’ He didn’t finish the sentence.

He talked a little of his childhood.

‘My dad has twenty-four kids, with three women. So it’s only us who lived in the one boma and we all grew up together. You feel like it’s good that you have a father, but it’s the other men around the family who are very influential, and in a way I was comfortable to ask questions. For societies that are organised and have men and older women taking care of young people, you get to grow faster, actually, than when you are with your parents. If you look at a child that was brought up by grandparents, they will most probably grow up faster in terms of development than a normal parent–son or child situation.’

A Canadian colleague had been listening and asked him how he got to school, since he lived in an isolated community.

‘At some point I used to walk about eleven kilometres each way. One of the things I remember always is my mother would wake me up at five in the morning and walk me halfway, and it’s always dark. And I know … it’s just recently that I think about it and I know that she’s scared too, because she’s walking me. Normally we would find elephants on the way, or you find a lion has made a hunt on the way, and you can’t go back or you have to wait until you at least get some light. So, you know, I used to remember we would have these elephant days. The way you have snow days in Canada where you can’t go to school? Well, we had elephant days. You know, it’s like,’ he made a gesture across the horizon, ‘hundreds in the herd, you can’t go, because you’re just about eight or nine years old. So you have to wait. You go to school and the teachers are mad at you because you are late.

‘We would arrive at school at seven or eight, and go until three and walk back again. Those early mornings are always very dangerous, and coming back in the evenings as well, because the times when you were travelling to school are the times when the animals are more active. That’s why children in those societies … it’s exhausting. They just get disorientated because they see risk every day. They see things that normal people don’t see. And they’re children, they are seven or eight or nine years old. So when you see children saying, “I don’t want to go to school anymore”, and people think they’re crazy, but the whole thing is just too stressful.’

In case you doubt the intensity of that last statement, his final story is breathtaking.

John was about eight years old, minding cattle with his six-year-old brother. On the way ho

me, meandering back to the boma with the cattle, they spotted some impala in the tall grass.

‘How many impala do you see?’ he asked his brother.

‘Six.’

‘No, there are seven.’

His brother’s eyes searched the long grass. ‘No. There are only six.’

‘No, there are seven.’

His brother paused again. ‘Where?’

John pointed out each of the seven impala. His brother watched where he pointed, but still couldn’t see the seventh.

‘I can’t see it. Where?’

So they began to walk towards it. They quietly pushed closer through the long savannah grass. They stepped straight into a pride of lions. Right into their space. Including females with cubs.

Immediately a female charged.

John recalled the event.

‘You know, one thing my father taught us, from the very early age, is that the only thing that runs in the bush is food. So we didn’t run. We stood still, just as he taught us.’

The female lion came straight for them, and just before she reached them she suddenly stopped. Right in front of them. So suddenly that it sent a shower of dust all over them that rose high into the air.

The two boys, aged six and eight, then slowly backed off and headed home.

After walking across hills and through isolated countryside in Lesotho for two weeks, I sent this email to a colleague the week I returned to my home on the Mornington Peninsula:

When I was in Africa this time, I didn’t see any wild animals at all. Not one. But since I’ve been home I’ve been woken each night by a strange noise. Around 1 or 2 a.m. I can hear a male lion calling - you know that short territorial moan that drops deep & resonates. It’s only about 300 metres away from my bed - it’s very clear. You think I’m being funny, don’t you. But there really is a lion about 300 metres away from my bed. True.

I didn’t have to look the lion in the eye and back away quite quickly; I was safe in bed. I never told my friend why there was a real lion calling in the night so close to my bed on the Mornington Peninsula – some things are best left hanging.

Travel Mistakes and How to Avoid Them, Part 4

An evaluation in Inteta, Mozambique brought me two useful travel lessons. To get there involved several flights – Melbourne, Perth, Johannesburg, then Maputo in Mozambique – in time to make a local flight north to Nampula, and then the long drive out to Inteta.

So everything went perfectly … until the first plane in Melbourne. It was delayed. Seriously delayed. This meant I arrived in Perth and looked out the window as we landed to see my flight take off for Johannesburg. Damn. I had to get to Johannesburg to be in Maputo on time, or I would miss the long trip out to the evaluation site. I went to the Qantas desk. The desk clerk had quite a few passengers to deal with, so I waited politely. Finally it was my turn. She announced I could have overnight accommodation, paid for by the airline. No, thanks, I have to be in Johannesburg tomorrow.

‘Sorry, it’s not possible.’ (Computer says no.) ‘But you have free accommodation at a hotel tonight.’

‘No, if I can’t get to Johannesburg tomorrow the entire trip will be a waste of time. Surely there must be some other way to get to Johannesburg?’

‘No, but you have FREE accommodation at a hotel overnight,’ she repeated, as if I had won a prize.

I found myself sitting on a bus waiting to leave for the free hotel accommodation. I was still desperate to get to Maputo and looked for alternative solutions. So I called South African Airways and explained the situation.

‘Where are you now?’

‘I’m still sitting in the bus just outside the terminal.’

‘Get off the bus and I will meet you.’

I stepped off the bus and she came out the doors almost immediately and took me back to the same Qantas desk, with the same desk clerk, where there were three business-class passengers.

‘OK, so we can fly you to Singapore, then you will fly Singapore Airlines to Johannesburg,’ the desk clerk informed us.

‘Really? How come you didn’t mention that when I asked you earlier?’

‘You didn’t yell loud enough.’

Travel idiot warning #45: Don’t yell and don’t bully staff – but be aware that there is often another way to get to where you’re going.

Many hours later I was sitting on the Singapore Airlines plane and realised I had another slight problem. My money and credit cards were not in my bag, but sitting on the couch at home. There’s always a best response to a situation, I told myself, and this was definitely a situation. So I thought it through. I didn’t actually need any money until I had to pay for my visa in Mozambique. Once I was in Mozambique I could borrow money from our office there. Right. Except I couldn’t borrow money from people inside the country if I was technically outside the country. So I formulated a plan. It was a good plan. It was a best-laid plan.

When I finally arrived in Maputo, I explained to the immigration officer that I didn’t have money, but my colleague was inside to pick me up, and he would have money. So, could I please leave my passport with him and go to get the money and come straight back.

He looked at me closely.

‘Alright,’ he said.

I knew it was a good plan. I was through. This was going well. I grabbed my luggage and went out into the thronging airport to look for the sign held by a colleague. I couldn’t see the sign. I couldn’t see the colleague. I waited. People left. Nobody was there. Nobody came. My passport was still back with the kind man in immigration, and I was outside. With no money. With a phone that didn’t work in Mozambique. The crowd began to thin and I was in a slight predicament. A friendly face had been watching me for a while.

‘Do you need some help?’

He looked friendly enough, but I wondered what this was going to cost me.

‘I have a slight problem …’

I explained the situation and he offered to call someone. It was Sunday morning. Many of the staff would have been at church, so most of the phones rang out. Eventually I found someone. I explained the situation and that the driver needed to bring some money for the visa.

‘He will be there in about thirty minutes.’

True enough, about thirty minutes later he arrived.

‘Are you ready to go?’

‘Yes, but … did you bring the money?’

‘What money?’

Another forty minutes later he returned with money. I then had to find my passport and the kind immigration man. I wandered back into immigration. No-one was there. I wondered how life could become so complicated. The airport that was normally so regimented and secure was like a school after the children had gone home. I was able to wander around freely through all the offices, but I couldn’t find anyone. Eventually I started knocking on different doors until I found someone and was able to sort it out. The process had taken hours. The man who helped me with his phone wouldn’t take any reimbursement. There are kind people the world over.

Travel idiot warning #18: Take money. It might be useful.

CHAPTER 27

South Sudan on the Brink of Civil War

South Sudan had been a troubled place for decades. So it was a positive sign late in 2013 to be part of an assessment to see if we could move from emergency relief to long-term community development.

My friend Keith had been part of relief efforts back in the 1990s, when South Sudan was still the south of Sudan and the people weren’t getting on particularly well with the Sudanese government. World Vision sent Keith to the middle of nowhere. Air drops of food packages were pushed out of the back of a transport plane into this middle of nowhere, and he would organise the food distribution with local Dinka groups. He went bush, sleeping in a thatch-roofed mud hut, made slightly less romantic by the sounds of rodents scratching and scrabbling around him at night. A typical day might involve finding someone who wanted a lift to a health centre because they had a spear in their leg or something. Local

disputes, you know.

He described the menu:

Monday – Goat and ugali

Tuesday – Goat and rice

Wednesday – Goat and ugali

Thursday – Goat and rice

Friday – Goat and ugali

Saturday – Goat and rice

Sunday – Special menu. Goat, with your choice of ugali or rice.

Ugali is a hard maize porridge like thick mashed potato. Only thicker.

His team had about twenty minutes’ notice if the Sudanese government was about to attack by air, and there was also a risk of land attacks. In the middle of one inky black night he awoke to gunfire all around. Keith peered out but couldn’t see what was happening. He crawled out of his quarters and hid in the night shadows at the back of his hut. Eventually two expats joined him and in whispers they discussed options. An attempt to run for the trees could draw attention. To stay here would mean being at their mercy.

As it turned out, running for the bush wouldn’t have gained anything. There was no attack. It was just some sort of celebration that began at midnight, and shooting guns in the air is apparently the way they roll.

So yeah, this wild place appealed, and finally I was going. To a now fully independent South Sudan, the world’s newest country. This meant flying into the capital city, Juba, in Central Equatoria, such an evocative name. I mean, the word ‘Equatoria’ sounds like it was made up for a 1930s boys’ own adventure story. I definitely wanted to go there.

From: Brett Pierce

Sent: 20/10/13

To: Kathleen Pierce

Subject: Hello in passing

Beyond the Vapour Trail

Beyond the Vapour Trail