- Home

- Brett Pierce

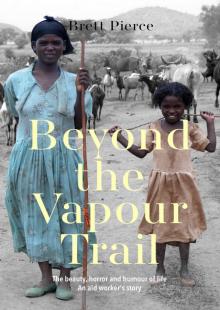

Beyond the Vapour Trail Page 5

Beyond the Vapour Trail Read online

Page 5

When the Minister of State for Refugees and Disaster Preparedness came to visit, she ‘banned’ radio stations from broadcasting news about the attacks. Father Mubiru stood up and said, ‘What the people need is not condoms and food, but security that is supposed to be guaranteed by the UPDF [Uganda People’s Defence Force]. What am I to tell my donors if the government does not do its job?’ So later the police stormed his radio station and shut it down. They claimed the station was alarming the population by sensationalising the attacks and causing people to flee their homes.

Father Mubiru later told local media, ‘We are trying to help people make decisions concerning their security, and to allow them to find their relatives … What the people of Teso need is the truth, it is only the truth which will solve this war situation. Lies will not.’

The following day, Wednesday, we conducted a number of focus groups. Our sub-team visited a school, reflecting on the progress of our education interventions with children and teachers. We then travelled to one of the small villages to listen to community members there. After we had finished our questions, I invited them to quiz us (as I often do).

‘We’ve been asking many questions. Perhaps you have some questions for us?’

There were a few questions, and then an older lady asked about child sponsorship.

‘Normally when someone writes a letter, there is an address in the top corner. But when the sponsors write, there is no address.’

We ask sponsors not to include their address for a number of reasons. The community listened politely as I talked about the efforts we take to protect their children. Then I added another perspective.

‘Sometimes when the sponsor’s address gets into the community the sponsor starts to receive lots of begging letters …’

As soon as the interpretation came through the whole group started laughing. This was clearly not a new idea, and I already knew that begging letters had been coming from this community.

I was enjoying the interactions with the different groups in the community. They were so earnest, so human, so welcoming. People gathered politely under some trees, mothers listening as they were nursing babies. Older women. Children out of school. Men with dignified faces. Every time they spoke they opened up with new insights about who they were, what was important to them, what could improve, what we could work on together.

We left the group and drove back to our evaluation base at a local school. As we arrived our project officer told us that there had been an attack on a vehicle by the LRA not far away. The LRA never use vehicles themselves due to some form of superstition, and prefer to travel on foot. This attack meant the rebels were getting closer. It was only a few kilometres away.

Things were about to fall apart.

CHAPTER 7

The LRA and a Young Girl

The road from the north beside our base became a one-way river of cars and trucks heading south. The more prosperous reached Soroti town first in their own vehicles, driving fast through the town as though they wanted to put a great distance between themselves and what they had seen. As the hours passed, we began to see trucks with people crammed on the back or clinging to the sides. You could glimpse their faces – whatever they were fleeing, it was serious. Many jumped off in Soroti and stayed in the town, out in the open, just wanting to be anywhere but where they’d been. This endless stream continued over a few days, until eventually people started arriving on foot, people with desperation and exhaustion in their eyes, carrying only the very youngest children; other quite small children had to walk.

By Wednesday afternoon we abandoned our evaluation and shifted to relief footing. With thousands of people filling up any park or open space in Soroti town, they now needed shelter, food, access to clean water and other basic supplies. Relief is first of all a logistics game: you have to assess, estimate the number of people requiring assistance, work out what is needed and where you will source it, and then how to get it to where it’s needed. Rapidly. It feels counterintuitive and slow, but it’s vital to get the logistics correct and coordinate all the efforts. Agencies work together brilliantly in these situations. Really – it’s impressive.

In a spare moment – some downtime, when frustratingly we could do nothing – a group of us were just sitting around the school. I interviewed some of the young staff about the work, including Albert Eregu and James Eniau, who worked in our program monitoring vulnerable children in the community. When life is interrupted by a crisis, people often begin to speak from the heart. James mentioned that he was one of forty children. His father had several wives, so for him to get any attention at all from his father was a rarity. It was clear that he felt that distance. One of his older sisters, his favourite sister, had died a few years before. When she was dying she had asked him to take care of her daughter. And so he did. He took her into his life, and into his heart. He was still only a teenager at the time, but he worked to take care of this little girl and loved her.

Then one day out of nowhere, word came that his niece’s father, who had abandoned his wife and daughter at birth, now wanted the girl to come to live with him. James shook his head as he told me this. She didn’t want to go. James didn’t want to lose her, but there was nothing he could do. This was her father. So she went to live with her father, who was married with other children. James sent money to them when he could to help take care of her needs. As weeks and months went past, she wrote to James and told him she was being treated badly by her stepmother. And then one day a message arrived to inform him that the girl was sick and needed attention and could he please send some money. It was a snake bite. He immediately sent money, but she was never taken to the health centre. She died.

It broke his heart. He decided when he finished university that he wanted to do something to help other children, so he had found work with our program here. He told me stories about a number of children he visited and who amazed him or were in special circumstances. One girl he mentioned in particular. She had come to the attention of our staff in the area. They started to visit and provide some assistance, and she was one of the children James monitored.

‘She lives with just her mother, and her mother is dying of AIDS. She is, ah! She is an amazing girl, who cares for her mother, and is always so positive. But lately, you know, I worry for her. She seems to have become despondent. She used to say that she wanted to be a nurse, but now she doesn’t smile anymore and says she will just be a soldier. You know, I think it just seems her way of showing she can no longer see the future.’

Something clicked inside me. I just knew I wanted to connect with this girl. I would sponsor her. Up until this point I had never sponsored a child, perhaps waiting for a special connection. Right at that moment I knew I wanted to help her. So I suggested that we put her in the sponsorship program. Yes, James had been visiting her anyway, providing the mother with antiretrovirals and other assistance and checking in on the girl, but a sponsor would mean someone else in her life. I didn’t tell him that I had decided to sponsor her myself. I asked if we could go and see her.

But that was not going to be simple.

The problem was, we had just heard that the LRA was now only a few kilometres away from us, and for us to reach this girl would mean driving towards them. Pauline, the Ugandan program officer in charge, was obviously very hesitant. As she deliberated, for no particular reason I felt confident she would let us go.

‘OK,’ she decided, ‘we will go tomorrow.’ Yes, it seemed like madness. But in all the chaos and numbers, an individual mattered. It was a beautiful kind of madness.

Later that day I needed internet and I found some at a nearby Youth With A Mission base. The staff were busy and left me in their office. A little two-year-old was crying just outside my door and everyone was busy, so I picked her up, and then as I typed she made herself peacefully at home on my lap. As the sun set the power suddenly shut down and I was sitting in almost total darkness, typing an email to my wife on my laptop, waiting for the

power to come back on.

From: Brett Pierce

Sent: 18/06/03

To: Kathleen Pierce

Subject: RE: Kate

Hey baby.

I miss you so much. I just had a little AIDS orphan in my lap as I was downloading my mail here in YWAM – she’s about 2 maybe and likes men and mzungus (white people) so she stopped crying as soon as I picked her up.

I’ll read your email when I’m not paying 700 shillings per minute and reply then.

The Lord’s Resistance Army stopped one of the committee member’s sons and burned his car, shot him through the neck and just clipped his ear with the next shot so he survived. They’re coming south – so the town is full of refugees. The LRA are about an hour away – but we’re monitoring closely.

Love you

Brett

I could barely type in the dark so I signed off and sent what I had written. Later that night I wrote more, but wasn’t able to send it until Friday.

From: Brett Pierce

Sent: 20/06/03

To: Kathleen Pierce

Subject: RE: Kate

Hey you.

Hope my quick email didn’t disturb you. The power went out and it was hard to type in the dark under pressure with 700 shillings a minute ticking by whilst online.

I visited a village today as part of the evaluation. It was kind of eerie, as there were refugees (well, Internally Displaced People technically) all along the road because the Lord’s Resistance Army was about an hour or two away. It’s a mess up north.

Anyway, the village was nice. The elders always welcome you in these settings before you can interact with the village – formal speeches and all.

Check this out for class sizes – Arabaka Primary:

P1 150 students aged 6-7, 1 teacher

Meet under tree (Imagine the attention span of 150 6yos outside!)

P2 80 students, 1 teacher

Meet under another tree

P3 53 students

p4 50 students, 1 teacher for P3 & P4.

Classroom - roof - no walls

P5 75 students

P6 57 students

P7 20 students, 2 teachers for P5, P6 & P7

The other classroom roof - no walls

No books. Not a single book. Most have textbooks to write on, the rest scribble on the ground. And libraries everywhere at home cull books every year …

There’s a girl I’m visiting tomorrow whose mother is dying of AIDS. She has been looking after her mother alone since she was 10 – she’s 12 now. She bathes her mother, feeds her, goes to school. The relatives abandoned them for some reason. I found out she’s not in the sponsorship program because we usually don’t enrol children after they turn 12. But surely we can bend the rules to fit around people, hey. She’s traumatised a bit – by her mother’s pain and stuff. Some days she wants to be a nurse or something, other days she wants to be a soldier because she can’t see a future. And people ring us and ask if these children are real.

The next day, Thursday afternoon, we drove out of Soroti, in the wrong direction, towards the LRA. We were the only vehicle on the road heading north, against a flood of vehicles and people on foot heading in the opposite direction. It was like the film Apocalypse Now, going upstream towards that space where the signal of civilisation peters out and you enter the white noise. Where there is no accountability.

We stopped and spoke to one of the families fleeing from the north, a woman with several children. Her eldest, a boy of about sixteen, was wheeling a bicycle with another child on it, and two live chickens hanging undignified from the handlebars by their feet. Several other children, some very young, were accompanying on foot. They were all clearly exhausted.

She was very emotional and complaining of hunger and walking for three days. She and her children had walked more than 30 miles. She was already in an IDP camp, and the LRA shot their security guard. So they fled. She doesn’t know where her husband is. They’ve slept on the side of the road. The youngest walking is maybe three.

‘Where are you going?’

‘I don’t know. Wherever my feet can take me.’

So many people were already living in IDP camps because of LRA attacks. When families abandon their homes for safety they can no longer grow their own food. Everything compounds. But they preferred to live in the camp than to ever have to face another LRA raid. It hinted of horror unimaginable. So did the strain on their faces. She told us that when the LRA attacked their camp she grabbed her children and whatever they could pick up as they ran and fled. They had been walking for three days without food. I gave her ten thousand shillings which seemed to lift her a bit. There was a market just down the road.

We drove further upstream into this flowing river of fleeing people, now beginning to thin out. Finally we pulled off the road into a small settlement. There were still people here. And strangely, they weren’t going anywhere. They were just calmly going about their business and ignored the people fleeing on the road nearby. Perhaps they didn’t think the LRA would come, since Kony’s army had never been this far south before. I couldn’t understand why they didn’t run like everyone else.

We came to a little building. Betty wasn’t there, she was out running an errand, but her mother was lying down just outside her home. Her name was Clere. Clere’s ‘home’ was a concrete block room, about two by three metres. Inside, the only furniture was a hessian bag stuffed with grass – which passed as a mattress for her to share with her daughter. There was a hoe and two cooking pots. Outside were two chickens and a spindly-looking garden tended by Betty. That was their world – just these possessions. And each other.

Clere tried to stand but was too tired. She was in the later stages of AIDS. I supposed she was probably another victim of an errant husband. So she was alone, with just her daughter to look after, until the sickness took its toll and her young daughter slowly began to look after her. How difficult must that transition have been for this mother.

Yet there was a beautiful dignity in her manner. And in the midst of our conversation Betty arrived. A big shy smile. A bright purple school uniform – the school uniforms in Uganda are usually in bright colours so that the children will love to wear them, I was told. And they certainly do.

Betty sat quietly and solemnly. We explained that we wanted to offer Betty a place in the child sponsorship program, and I added that I wanted to sponsor her myself. They were both very thoughtful. After a while, Betty started smiling. She couldn’t stop smiling and kind of shaking her head in disbelief. She would stare into the distance thoughtfully, and then smile even more.

Clere thought for a while and then responded in her own way. She decided to give me a gift. One of her chickens. One of their two chickens.

I was completely humbled. This was by far the most generous gift I have ever been offered. Clere was not a passive recipient, but a woman of dignity and generosity in incredibly hard circumstances. To me the gift also meant I wasn’t the patronising stranger – her gift transformed that into something more beautiful. It made us equals who shared a concern for a young girl. As a parent, what must it have been like for her, day after day, to worry about her daughter’s future and know there was nothing she could do to be there for her?

I accepted her gift, and we remained equals. Human dignity is a sacred thing.

But that meant Betty had to catch the chicken.

What followed was pandemonium. Like a Looney Tunes cartoon, chicken and girl would run past us and disappear into bushes or around a building, only to appear running in the opposite direction. Eventually the chicken, legs tied, sat beside me, blinking. And I wondered what in hell’s name I was going to do with it. My first ever chicken.

Betty got down on her knees in front of me, took my hands and spoke very earnestly in her native Ateso and bits of broken English. I didn’t understand all the words, but you know when something comes from the heart. We couldn’t stay long. From deep inside I had an overwhelming urge to say t

o her, ‘Whatever happens, don’t give up, don’t ever give up.’ Now that might sound nice to read in a story, but sitting there with everyone around me it seemed profoundly melodramatic and I felt stupid. I said it anyway. I looked into her dark eyes and wondered about her life, her every day of waking early, gathering water, starting the fire if they had food to eat, tenderly bathing her mother, sweeping the dust around their home, rushing to school, trying to concentrate, running home to check on her mother, running back to school, coming home to tend the garden … all the while watching her mother fade away, her health and tenuous grip on life fading – the stumbles, the just-sitting-down-for-a-moment to catch her breath. The days she didn’t go anywhere. Betty was twelve, and she carried this. Their family had cut contact with them for some reason and that had isolated these two human beings, clinging to each other on the edge of a village.

Betty Alajo was still smiling radiantly when I left, but I thought I glimpsed a little sadness as well. But at least I was another adult in her life who was committed to her. Children need to know they matter to someone. We drove off, the bewildered chicken in the boot. I pictured myself at quarantine in Australia trying to explain this live chicken sitting in my hand luggage. I gave the chicken away. I later heard it ran away and was never caught again. It really was a fast chicken.

I added to my unsent email:

OK next day.

We’re evacuating in the morning. The LRA were only 14 kilometres away this morning. They kidnapped about 12 children from the local convent between 7 & 14. The youngest woke up crying and asked to go with them because he didn’t know what was going on. There are 5000 refugees in Soroti town where we are. We drove out about 5 kilometres today so I could see this girl. It was strange because all the refugees were going in the opposite direction. So I’m now a sponsor. She’s lovely, and her name is Betty Alajo. She looks after her mother who is dying of AIDS.

Beyond the Vapour Trail

Beyond the Vapour Trail